HEAT OF THE MOMENTUM

I stared at the note for quite awhile, trying to figure out what it meant. At first I figured Jimmy must have left the bundle of shocks, since his father stocked such things at his body shop. But there was no way a college student like Jimmy would misspell a common word like “problem”, drunk or sober. And the fact that most of the words were spelled correctly pretty much eliminated Sal. Which meant that the shock-absorber care package must have been Beck’s doing, and as soon as I realized this, I hustled the bundle into the house and stashed it in my room. Obviously Beck’s creative juices hadn’t started flowing until Jimmy and I left the previous night, and he’d eventually come up with some sort of solution to the braking problem. It also seemed that he had enough confidence in his idea to act on it. At the time I had no idea what sort of solution Beck could’ve come up with for our “problum”, I just hoped it turned out to be as sensible in the light of day as it seemed when Beck came up with it the night before. The bundle of shocks I stuck under my bed were relatively new, but covered with dust and road-grime. They obviously hadn’t come from an all-night auto parts store. I guessed that Beck had been struck with a burst of twisted inspiration after Jimmy and I left, then spent the rest of the night staggering around town with his brother, a bumper jack, and a crescent wrench. Looking for donor to contribute some hardware to our cause. It seemed as if they’d found one, too. And if someone was going to wake up that morning to a car that was mysteriously missing all four shock absorbers, I hoped like hell Beck’s plan was worth it.

But I never actually asked Beck where the shocks came from, and he never volunteered the information. I didn’t consider it critical to the mission.

I did, however, call him later in the day to ask what I was supposed to do with the shocks. His first suggestion was that I stick them up my ass. I assumed that he was just in a bad mood from a hangover, since there was no way an assfull of shock absorbers would help to slow a fast-moving Rocket Car. So I kept interrogating him until he finally remembered the details of his Grand Plan, and agreed to meet me at the scrapyard later on. When he finally showed up at the gates to the yard he looked like hammered shit, but I expected as much. Go spend a night getting drunk and stealing auto parts and see how you feel the next day. But he was also reasonably coherent, and described his idea while we walked out to the weedy corner of the field where the Rocket Car was still perched on cinderblocks.

And I have to admit, it was good. Real good. Better than anything we’d figured out up to that point, anyway. But the best part (to me, anyway) was that it didn’t involve me stealing anything else that my father might notice.

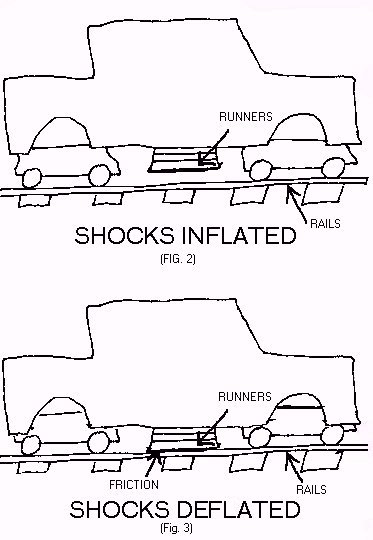

Beck’s idea was simple, elegant, and easy to put into practice. I’d install the air shocks on the Rocket Car normally, just as if the car would be riding on pavement instead of rails. But I’d also bolt a pair of wooden beams onto the belly of the car, runners that were placed exactly between the front and rear train wheels. Each runner would be thick enough to reach almost all the way down to the tracks, and the bottom would be covered with rubber cut from old tires. The effect would be that the car would roll freely while the air shocks were inflated, with the twin runners suspended inches above the steel tracks. When it was time to stop the car, the pilot would activate a release valve which would dump the air from all four shock absorbers simultaneously. The car would drop until its entire weight was resting on the runners, which would be pressing into the railroad tracks. This would provide two brake shoes three feet long, pushed against the track under the weight of the car’s body, providing a huge amount of stopping-power. And since the wheel flanges would also still be firmly on the tracks, the car would remain traveling in a straight line.

Beck’s idea was simple, elegant, and easy to put into practice. I’d install the air shocks on the Rocket Car normally, just as if the car would be riding on pavement instead of rails. But I’d also bolt a pair of wooden beams onto the belly of the car, runners that were placed exactly between the front and rear train wheels. Each runner would be thick enough to reach almost all the way down to the tracks, and the bottom would be covered with rubber cut from old tires. The effect would be that the car would roll freely while the air shocks were inflated, with the twin runners suspended inches above the steel tracks. When it was time to stop the car, the pilot would activate a release valve which would dump the air from all four shock absorbers simultaneously. The car would drop until its entire weight was resting on the runners, which would be pressing into the railroad tracks. This would provide two brake shoes three feet long, pushed against the track under the weight of the car’s body, providing a huge amount of stopping-power. And since the wheel flanges would also still be firmly on the tracks, the car would remain traveling in a straight line.

When Beck finished explaining his idea, I stood there with my mouth hanging open. Actually we both stood there with our mouths open, but while my jaw was flopping due to surprise, Beck’s was caused by a powerful hangover that was still affecting his motor control. I must admit, though, I was pretty impressed with his thinking. We’d talked about dozens of ways to stop the rocket car the previous evening, but nothing that even came close to Beck’s plan. It was simple to build, easy to install, and stood a fair chance of working. I knew that sooner or later I’d have to talk to Jimmy about the whole thing, but that didn’t stop me from getting to work installing the air shocks on the Chevy as soon as Beck slouched out of the scrapyard and went home.

I worked on the car for the rest of the afternoon, wanting to get as much done as I could on a Sunday, while the yard was closed. By the end of the day, I had the shocks installed on the car and a pair of three-foot-long runners made from sections of 2 x 4 bolted together to make them thick enough to reach the rails. All that was left to do was bolt the runners to the car frame and arrange the air hoses for the shock absorbers, and the car would be ready to test. It was THEN that I finally called Jimmy and asked him to come down to the yard. Talking to him sooner would’ve been the sensible thing to do, but I didn’t want to take a chance that he’d come up with some laughably obvious reason the brake-runner system wouldn’t work. At the time, my thinking on the subject was pretty clear: There were only two ways were going to be able to stop the Rocket Car, either by using a drogue chute or by Beck’s braking system. And although I wasn’t too keen on the idea of taking one of my Dad’s parachutes, I’d do it if it was the only way to get the Rocket Car to work. But even if we did use a drogue chute, the car would need an additional braking system anyway. A parachute will slow a car, but it won’t stop it. You still need regular brakes for that.

The way I figured it, we’d need Beck’s idea no matter what happened. So I decided to show Jimmy the braking system I was building and see what he thought. If he pointed out some reason why it was completely foolish, I’d show him Dad’s parachute collection, then tell him that the brake runners were the standby system, and we were actually going to use a parachute to slow the car to reasonable speed.

It not only sounded reasonable, but it kept me from looking like a total asshole.

All my planning was unnecessary, though. When Jimmy heard me describe the rail-braking system and saw what I’d done to the car so far, he was very impressed. I think he was also a little pissed off that Beck had come up with the idea, and not him. But here’s a thought that never occurred to me back in 1978, and to be honest, I’m glad it didn’t: We never really had any proof that it was Beck who came up with the idea. For all we know, it was Sal who dreamed up the notion of using runners to stop the car. Yes, yes, I know, it’s a ridiculous thought. Like having your pet hamster wake up one morning with a revolutionary process for splitting atoms. After all, we’re talking about the guy who wanted the pilot of the Rocket Car to hoist a goddamned anchor out the window to slow down.

Still, you never know. And Jimmy, if you’re reading this, I’m sorry I even brought it up now. I know you’ll lose some sleep over it. But I couldn’t resist.

Anyway, Jimmy did give the braking system his stamp of approval, and I never had to admit that Dad had a bunch of parachutes stashed in the shed. The only reservation Jimmy had about the system was one that should’ve been obvious to me from the start: heat. If the car were traveling as fast as we expected it to, rubber-coated planks pressing against metal rails would probably get hotter than hell. On the other hand, this was basically the same system used by every car on the road, as well as racing cars. Drum and disc brakes are essentially nothing more than pads or shoes pressing against moving pieces of steel to stop the car. The only difference between their system and ours was that standard brakes pressed brake pads against steel that was spinning, while ours used steel moving in a straight line. And even though our car would be traveling a lot faster than most, we had much more overall braking surface. So Jimmy and I talked about ways to cool the runners for awhile, just in case heat buildup turned out to be a real problem. Actually, I think Jimmy might have made the heat problem sound worse than it really was, just so Beck wouldn’t get ALL the credit for solving the brake problem. But to give credit where it’s due, we did wind up with a heat problem, so whatever Jimmy’s motivations might have been, it’s a good thing I listened to him.

Then again, if I’d ignored him, I doubt it would’ve changed the final outcome too much.

With the conceptual details taken care of, all that was left was construction. Even though the braking and brake-cooling systems were the hardest part of the car to fabricate, it didn’t take long to get them built and installed. Bolting the runners to the car frame was quick work, and even though it took a little doing to get the air-dump valve connected to all four shock absorbers, I had plenty of materials to work with laying around the scrap yard. After removing the valve stems from the air inlets to the shocks, I attached sections of air-compressor hose to the valves themselves. The other ends of the hoses ran to an air valve that started life as the door-opening lever on a city bus. With the lever in the “open” position, all four shocks could be inflated from a single air inlet near the dump lever. Once the shocks were pressurized, releasing the lever kept them inflated until the lever was pushed again.

I first tested the air-valve system on Tuesday afternoon, and when I saw that it worked the way it was supposed to, I immediately called Beck. He came to the yard with Sal, and the three of us took turns raising and lowering the car for almost an hour before the novelty wore off. Despite the fact that it wasn’t very exciting to watch, there was something distinctly satisfying about seeing the system work the way it was supposed to. Of course Beck was more anxious to “take the car for a spin” than ever, and he actually got a little pissed off when I pointed out that we weren’t out of the woods yet. There was still a heat problem to deal with, but this detail didn’t cut much ice with Beck. He was positive that it wouldn’t be a problem, which meant that our next step was to take the Chevy out and light the rocket. So rather than dwell on the heat problem, I said “Haul it out WHERE, and light the rocket with WHAT?”

That took the wind out of his sails in a hurry.

See, we still hadn’t considered how we were going to ignite the JATO, but to be honest, this wasn’t a major sticking point. There was a rubber plug in the end of the exhaust nozzle of the rocket I’d inspected, and it seemed logical to assume that some sort of igniter plugged into the hole. Probably an electrical fuse, something along the lines of the igniters used for model rockets. Whatever fueled the rocket (ammonium perchlorate, I later found out) was no doubt highly flammable, and shouldn’t be too tough to ignite.

But I knew I could come up with something better than a fuse.

A much bigger problem was the launch site. Beck got sulky and petulant when I pointed out that we had no idea where we’d actually run the car, but he didn’t argue too much. Even if I agreed to hoist the car onto Dad’s flatbed right then and there and drive around searching for a spot to use, I’m sure Beck would’ve realized how dumb the idea was before we even got out of the yard. So I put Beck in charge of finding a suitable launch site, which I’d have done even if he wasn’t being a royal pain in the ass and keeping me from my work. His Dad’s four-wheel drive was the perfect vehicle for location-scouting, and he and Sal were more familiar with the surrounding desert than anyone I knew. Beck and Sal headed for the gates deep in conversation, and I got back to work.

The brake-cooling system I ended up building was pretty cheesy, I’ll be the first to admit that. But since we weren’t even sure it was necessary, I didn’t want to spend a lot of time messing with it. I ran a length of garden hose along each wooden runner, near the point where the runner was attached to the car. Took the ends near the front of each runner, and led them into the empty engine compartment. I tied off the ends under the car, then punched holes along the sections near the runners with an awl. Water entering the ends in the engine compartment would leak out through the perforations, soaking the runners and pads.

I told you it was pretty cheesy.

The only part of the cooling arrangement that even came close to sophistication was the result of a brainstorm that came to me while I was strapping a five-gallon jerry can under the hood of the Rocket Car. I started putting the sprinkler system together with the idea that we’d simply open a valve before launch, letting water leak out of the hoses and onto the runners for the duration of the run. But while I was attaching the jerry can, a better method occurred to me. Instead of attaching the garden hoses to a valve, I drilled a pair of holes directly into the top of the jerry can, and fed the hoses through the holes. Then I drilled a third, smaller hole, and connected another hose from the jerry can to the air-dump handle for the shock absorbers. I sealed all the hose connections with massive amounts of rubber cement, then called it quits for the day.

No word from Beck or Sal that night, so I assumed finding a launch site wasn’t as easy as they’d thought it would be.

When I checked the Rocket Car the next day, the rubber cement sealant had dried to the consistency of a hockey puck, so I tested the entire system. I filled the air shocks from Dad’s portable compressor, then closed the dump valve. Filled the jerry can with water, and screwed the top down tight. Said a quick prayer, and hit the dump-valve lever. There was a slight hiss as the air rushed out of the shocks, through the dump valve. But instead of being vented into the open, the last air-hose I’d installed directed the escaping air into the jerry can full of water under the hood, forcing water out through the sprinkler hoses. When I checked under the car there was an impressive puddle, and water was still jetting out of the holes in the garden hoses.

I was thrilled beyond words.

And when Jimmy saw the whole system in action a few days later, he said he was “..really impressed with my application of Bernoulli’s Principle.” Hell, I didn’t even know that the Italians built rocket cars.

Next: “Affatus Interruptus”

fantastic! as a former small town boy with energy to burn i can relate 100%.

if you’re ever bored i can send you a story not as involved but equally amusing in its underlying theme of ‘boys will be boys’

enjoy life!

Sure, feel free to post it.